|

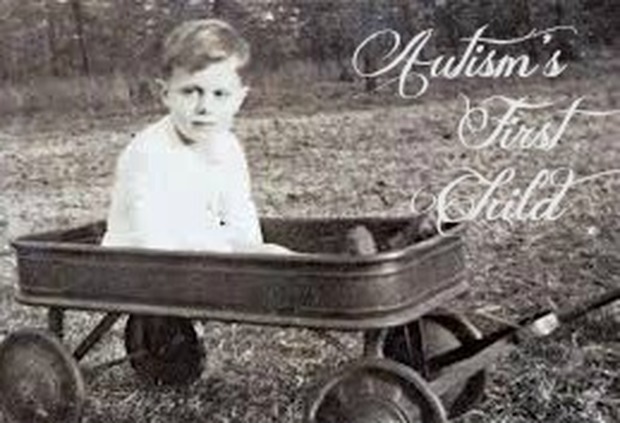

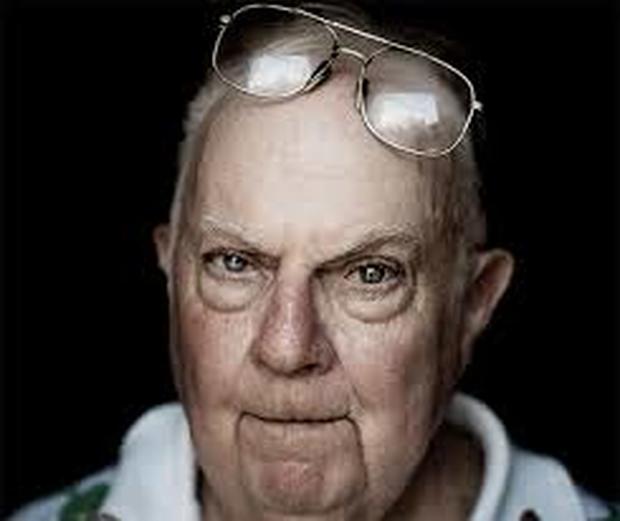

It seemed fitting that for Autism Awareness Month, I introduce you to the first person ever diagnosed with autism. This is not my story, but one from The Atlantic, and was published in August of 2010. I have only included parts about "Autism's First Child", Donald, but the whole article gives a bigger picture of autism in general, and autism in adulthood (something rarely talked about or looked at). I haven't changed the wording at all, the only thing I have done here is to condense the story. The full story can be read here. Meet Donald Gray Triplett, of Forest, Mississippi. He was the first person ever diagnosed with autism. In 1951, A Hungarian-born psychologist, mind reader, and hypnotist named Franz Polgar was booked for a single night’s performance in a town called Forest, Mississippi. Polgar was lodged at the home of one of Forest’s wealthiest and best-educated couples, who treated the esteemed mentalist as their personal guest. Polgar’s all-knowing, all-seeing act had been mesmerizing audiences in American towns large and small for several years. But that night it was his turn to be dazzled, when he met the couple’s older son, Donald, who was then 18. Oddly distant, uninterested in conversation, and awkward in his movements, Donald nevertheless possessed a few advanced faculties of his own, including a flawless ability to name musical notes as they were played on a piano and a genius for multiplying numbers in his head. Polgar tossed out “87 times 23,” and Donald, with his eyes closed and not a hint of hesitation, correctly answered “2,001.” Indeed, Donald was something of a local legend. Even people in neighboring towns had heard of the Forest teenager who’d calculated the number of bricks in the facade of the high school—the very building in which Polgar would be performing—merely by glancing at it. According to family lore, Polgar put on his show and then, after taking his final bows, approached his hosts with a proposal: that they let him bring Donald with him on the road, as part of his act. The offer was politely, but firmly declined. What the all-knowing mentalist didn’t know, however, was that Donald, the boy who missed the chance to share his limelight, already owned a place in history. His unusual gifts and deficits had been noted outside Mississippi, and an account of them had been published—one that was destined to be translated and reprinted all over the world, making his name far better-known, in time, than Polgar’s His first name, anyway. Donald was the first child ever diagnosed with autism. Identified in the annals of autism as “Case 1 … Donald T,” he is the initial subject described in a 1943 medical article that announced the discovery of a condition unlike “anything reported so far,” the complex neurological ailment now most often called an autism spectrum disorder, or ASD. At the time, the condition was considered exceedingly rare, limited to Donald and 10 other children—Cases 2 through 11—also cited in that first article. His full name is Donald Gray Triplett. He’s 77 years old. And he’s still in Forest, Mississippi. Donald was institutionalized when he was only 3 years old. Records in the archives at Johns Hopkins quote the family doctor in Mississippi suggesting that the Tripletts had “overstimulated the child.” Donald’s refusal as a toddler to feed himself, combined with other problem behaviors his parents could not handle, prompted the doctor’s recommendation for “a change of environment.” In August 1937, Donald entered a state-run facility 50 miles from his home, in a town then actually called Sanatorium, Mississippi. The place wasn’t designed or operated with a child like Donald in mind, and according to a medical evaluator, his response upon arrival was dramatic: he “faded away physically.” At the time, institutionalization was the default option for severe mental illness, which even his mother believed was at the root of Donald’s behavior: she described him in one despairing letter as her “hopelessly insane child.” Being in an institution, however, didn’t help. “It seems,” his Johns Hopkins evaluator later wrote, “he had there his worst phase.” With parental visits limited to twice a month, his predisposition to avoid contact with people broadened to everything else—toys, food, music, movement—to the point where daily he “sat motionless, paying no attention to anything.” He had not been diagnosed correctly, of course, because the correct diagnosis did not yet exist. Very likely he was not alone in that sense, and there were other children with autism, in other wards in other states, similarly misdiagnosed—perhaps as “feeble-minded,” in the medical parlance of the day, or more likely, because of the strong but isolated intelligence skills many could demonstrate, as having schizophrenia. Donald’s parents came for him in August of 1938. By then, at the end of a year of institutionalization, Donald was eating again, and his health had returned. Though he now “played among the other children,” his observers noted, he did so “without taking part in their occupations.” The facility’s director nonetheless told Donald’s parents that the boy was “getting along nicely,” and tried to talk them out of removing their son. He actually requested that they “let him alone.” But they held their ground, and took Donald home with them. Later, when they asked the director to provide them with a written assessment of Donald’s time there, he could scarcely be bothered. His remarks on Donald’s full year under his care covered less than half a page. The boy’s problem, he concluded, was probably “some glandular disease.” Donald, about to turn 5 years old, was back where he had started. Most likely Donald's name would never have entered the medical literature had his parents not had both the ambition to seek out the best help for him, and the resources to pay for it. Mary Triplett had been born into the McCravey family, financiers who had founded and still controlled the Bank of Forest. She married the former mayor’s son, an attorney named Oliver Triplett Jr. With a degree from Yale Law School and a private practice located directly opposite the county courthouse. Their first son, Donald, was born in September 1933. A brother came along nearly five years later, while Donald was in Sanatorium. Also named Oliver, the baby stayed behind with his grandparents in Forest when, in October 1938, the rest of the family boarded a Pullman car in Meridian, Mississippi, headed for Baltimore. Donald’s parents had secured him a consultation with the nation’s top child psychiatrist at the time, a Johns Hopkins professor named Dr. Leo Kanner. Kanner (pronounced “Connor”) had written the book, literally, on child psychiatry. Aptly titled Child Psychiatry, this definitive 1935 work immediately became the standard medical-school text, and was reprinted through 1972. Kanner would always seem slightly perplexed by the intensity of the letter he had received from Donald’s father in advance of their meeting. Before departing Mississippi, Oliver had retreated to his law office and dictated a detailed medical and psychological history covering the first five years of his elder son’s life. Typed up by his secretary and sent ahead to Kanner, it came to 33 pages. Many times over the years, Kanner would refer to the letter’s “obsessive detail.” Excerpts from Oliver’s letter—the outpourings of a layman, but also a parent—now hold a unique place in the canon of autism studies. Cited for decades and translated into several languages, Oliver’s observations were the first detailed listing of symptoms that are now instantly recognizable to anyone who knows autism. It is not too much to say that the agreed-upon diagnosis of autism—the one being applied today to define an epidemic—was modeled, at least in part, on Donald’s symptoms as described by his father. The surviving medical records of that initial visit contain a notation preceded by a question mark: schizophrenia. It was one of the few diagnoses that came even close to making sense, because it was clear that Donald was essentially an intelligent child, as a person exhibiting schizophrenia might easily be. But nothing in his behavior suggested that Donald experienced the hallucinations typical of schizophrenia. He wasn’t seeing things that weren’t there, even if he was ignoring the people who were. Kanner kept Donald under observation for two weeks, and then the Tripletts returned to Mississippi—without answers. Kanner simply had no idea how to diagnose the child. He would later write to Mary Triplett, who had begun sending frequent updates on Donald: “Nobody realizes more than I do myself that at no time have you or your husband been given a clear-cut and unequivocal diagnostic term.” It was dawning on him, he wrote, that he was seeing “for the first time a condition which has not hitherto been described by psychiatric or any other literature.” He wrote those lines to Mary in a letter dated September 1942, almost four years after he’d first seen Donald. Perhaps hoping to allay her frustration, Kanner added that he was beginning to see a picture emerge. “I have now accumulated,” he wrote, “a series of eight other cases which are very much like Don’s.” He hadn’t gone public with this, he noted, because he needed “time for longer observation.” He had, however, been working on a name for this new condition. Pulling together the distinctive symptoms exhibited by Donald and the eight other children—their lack of interest in people, their fascination with objects, their need for sameness, their keenness to be left alone—he wrote Mary: “If there is any name to be applied to the condition of Don and those other children, I have found it best to speak of it as ‘autistic disturbance of affective contact.’” Kanner did not coin the term autistic. It was already in use in psychiatry, not as the name of a syndrome but as an observational term describing the way some patients with schizophrenia withdrew from contact with those around them. Like the word feverish, it described a symptom, not an illness. But now Kanner was using it to pinpoint and label a complex set of behaviors that together constituted a single, never-before-recognized diagnosis: autism. (As it happens, another Austrian, Hans Asperger, was working at the same time in Vienna with children who shared some similar characteristics, and independently applied the identical word--autistic to the behaviors he was seeing; his paper on the subject would come out a year after Kanner’s, but remained largely unknown until it was translated into English in the early 1990s.) Donald lives alone now in the house his parents raised him in. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Donald’s life is that he grew up to be an avid traveler. He has been to Germany, Tunisia, Hungary, Dubai, Spain, Portugal, France, Bulgaria, and Colombia—some 36 foreign countries and 28 U.S. states in all, including Egypt three times, Istanbul five times, and Hawaii 17. He’s notched one African safari, several cruises, and innumerable PGA tournaments. It’s not wanderlust exactly. Most times, he sets six days as his maximum time away, and maintains no contact afterward with people he meets along the way. He makes it a mission to get his own snapshots of places he’s already seen in pictures, and assembles them into albums when he gets home. He is, in all likelihood, the best-traveled man in Forest, Mississippi. This is the same man whose favorite pastimes, as a boy, were spinning objects, spinning himself, and rolling nonsense words around in his mouth. At the time, he seemed destined for a cramped, barren adulthood—possibly lived out behind the windows of a state institution. Instead, he learned to golf, to drive, and to circumnavigate the globe—skills he first developed at the respective ages of 23, 27, and 36. In adulthood, Donald continued to branch out. For a time, Donald’s care was literally shifted out into the community. Kanner believed that finding him a living situation in a more rural setting would be conducive to his development. So in 1942, the year he turned 9, Donald went to live with the Lewises, a farming couple who lived about 10 miles from town. His parents saw him frequently in this four-year period, and Kanner himself once traveled to Mississippi to observe the arrangement. He later said he was “amazed at the wisdom of the couple who took care of him". The Lewises, who were childless, put Donald to work and made him useful. “They managed to give him suitable goals,” Kanner wrote in a later report, " They made him use his preoccupation with measurements by having him dig a well and report on its depth. When he kept counting rows of corn over and over, they had him count the rows while plowing them. On my visit, he plowed six long rows; it was remarkable how well he handled the horse and plow and turned the horse around". Kanner’s final observation on this visit speaks volumes about how Donald was perceived: “He attended a country school where his peculiarities were accepted and where he made good scholastic progress.” But he never could count bricks. This, it turns out, is a myth.

Donald explained how it had come about only after we’d been talking for some time. It had begun with a chance encounter more than 60 years ago outside his father’s law office, where some fellow high-school students, aware of his reputation as a math whiz, challenged him to count the bricks in the county courthouse across the street. Maybe they were picking on him a little; maybe they were just seeking entertainment. Regardless, Donald says he glanced quickly at the building and tossed out a large number at random. Apparently the other kids bought it on the spot, because the story would be told and retold over the years, with the setting eventually shifting from courthouse to school building—a captivating local legend never, apparently, fact-checked. A common presumption is that people with autism are not good at telling fibs or spinning yarns, that they are too literal-minded to invent facts that don’t align with established reality. On one level, the story of Donald and the bricks demonstrates again the risks inherent in such pigeonholing. But on another level, it reveals something unexpected about Donald in particular. At the time of that episode, he was a teenager, barely a decade removed from the near-total social disconnect that had defined his early childhood. By adolescence, however, it seems he’d already begun working at connecting with people, and had grasped that his math skills were something that others admired. We know that, because we finally asked him directly why he’d pulled that number out of the air all those years ago. He closed his eyes to answer, and then surprised us a final time. Speaking as abruptly as ever, and with the usual absence of detail, he said simply, and perhaps obviously, “I just wanted for those boys to think well of me".

3 Comments

Sarah

4/9/2014 09:57:29 pm

wow

Reply

Amy-Lyn

4/10/2014 12:10:41 am

I know, isn't it amazing. I love that the "obsessive" 33 page note the father wrote to Dr. Kanner was the first list of early childhood symptoms of autism. I think it's an amazing piece to this story, and that without his observations, warming signs for autism (and being able to get early intervention) would have been delayed by who knows how many years.

Reply

Lauren

6/17/2023 10:29:37 am

Rest In Peace, Mr. Triplett.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Hi, I'm Amy-Lyn! I am the lady behind this here blog! I live in the sticks with my animals, my super handsome husband, and my

3 amazing kids! Here you'll find things from recipes (gluten-free, paleo, and strait up junk food!), DIY ideas, thoughts on raising a son with autism, and whatever else pops into my brain! : ) Read more about me by clicking here! Want to Stay Connected?

Find What

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed